The Next Generation of Visual-Motor Assessment

Executive Summary

Visual-motor integration (VMI) is essential for life and academic success and has well-established links with many learning and developmental challenges. This makes trusted assessment vital for practitioners. Yet, traditional assessment tools and practices have not kept pace with technology or with how modern clinics and educational settings operate.

This whitepaper introduces a new era in VMI assessment with the Psymark Visual Motor Abilities Test.

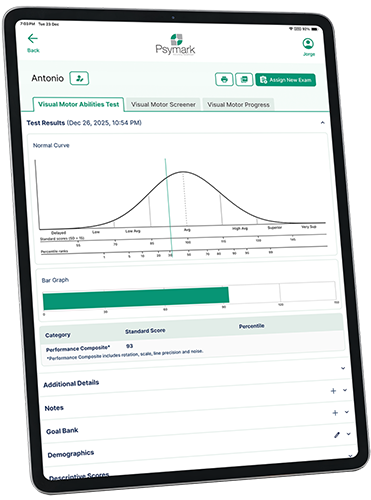

The Psymark Visual Motor Abilities Test (VMAT) is the first fully digital, self-scoring VMI assessment on the market. The VMAT leverages patented algorithms and up-to-date standardized norms to deliver an evaluation that is rapid, objective, and reliable. Built for occupational therapists, school psychologists, and other practitioners, VMAT is offered as a full-service iPad App, currently for ages 4-9.

Unlike traditional paper-pencil tests, the VMAT assessment is able to capture nuanced motor data in real time, offering deeper insights into a child’s motor functioning. In addition, the VMAT is the first tool to offer a goal bank to assist in the development of a child’s individualized education plan (IEP), treatment plan, or early intervention. The VMAT empowers professionals in their work to identify needs earlier, provide more precise intervention, and offer an engaging, meaningful experience to examinees. The VMAT brings together reliable research, cutting-edge technology, and best practices in VMI assessment for today’s educational and clinical environments.

I. Background

It is helpful to have a common definition of visual-motor integration (VMI) and to understand its relationship to eligibility for services when there are identified challenges. VMI is the coordination between what an individual sees and how this translates into precise movement. This occurs by perceiving visual input, processing the information, and coordinating a motor response—such as eye-hand coordination and gross and fine motor coordination (Schneck et al., 1996; Cornhill et al., 1996; Carsone et al., 2021).

Being able to control hand movements through vision is necessary for a wide range of academic and non-academic tasks. It is critical for everyday functions like eating and dressing. It is foundational in academic skills, such as handwriting, reading, and finger counting (Khatib et al., 2022; Carlson et al., 2013, Dere, 2019; Dohla & Heim, 2016; Khatib et al., 2022).

In particular, VMI directly relates to the ability to write, which is an essential component of literacy and a fundamental element in school and career success. Dysgraphia, commonly defined as a neurological condition affecting handwriting and fine motor skills, is common in students and patients with neurodevelopmental delays, learning disabilities, and other conditions. VMI has been associated with reading ability, and visual-motor skill deficits are often present with dyslexia (Dohla & Heim, 2016; Khatib et al., 2022). In addition to an association with reading, links have been found between visual-motor skills and school readiness, with a strong connection between VMI and math skills for younger children (Khatib et al., 2022).

A. Special Education and Other Services Eligibility

Current and trending data show that eligibility for special education services is rising (National Center for Educational Statistics [NCES], n.d.; Arundel, 2025; Blad, 2025). Just in the 2023-2024 school year, nearly 8 million students in the US were eligible for special education services (Arundel, 2025). This represents a 3.4% increase from the previous year, with approximately 15% of all public school students eligible for special education. Consequently, there is a rise in screening and assessment for special education and related services, including the evaluation of visual-motor skills.

Occupational therapists, school psychologists, clinical psychologists, physicians, researchers, and others routinely use visual-motor assessments to diagnose, treat, or research visual processing, visual-motor integration, memory, cognition, attention, and neurological deficits indicative of various disabilities, as well as other medical and psycho-educational conditions (Pieters et al., 2012; Schlooz & Hulstijn, 2012; Volker, et al., 2010; Brossard-Racine et al., 2012; Sutton, et al., 2011; Carames et al., 2022; Wuang & Su, 2009; Schultz, et al., 1998; Keane et al., 2016; Lo et al., 2015; Buchhave et al., 2008; Cormack et al., 2004; Kluger et al., 1997; Maeshima et al., 2004; Palmqvist et al., 2010).

Such conditions include:

● Learning Disabilities

● Autism Spectrum Disorder

● Traumatic Brain Injury

● Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

● Intellectual Disorders

● Tourette Syndrome

● Prader-Willi Syndrome

● Schizophrenia

● Parkinson’s

● Alzheimer’s

● Mild Cognitive Impairment

Visual-motor integration is crucial for a wide range of skills and VMI difficulties are present in many conditions, which necessitate assessment. We explore this next.

II. The Arena of VMI Assessment

There are important factors and considerations in the assessment of VMI. Covered in this section are the limitations of current VMI assessment and what the future holds.

A. Limitations of Traditional Assessments

The ability to copy geometric shapes is a key indicator and measure of VMI, linking visual perception (seeing) with fine motor execution (writing/drawing) (Beery & Beery, 2010; Bender, 1938; Brannigan & Decker, 2003). Common assessment tools include the Beery Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration, the Developmental Test of Visual Perception-Third Edition, and the Bender Gestalt Test. These tests use a paper-and-pencil format for measuring how well an individual can replicate progressively challenging geometric shapes from a model to gain insight into their visual-motor abilities.

Following completion, accurate scoring requires the examiner to score each drawing by hand using tools such as rulers and protractors, and then reviewing examples presented in a test manual as guidance. Historically, visual-motor tests have faced significant reliability challenges, particularly inter-scorer reliability. While well-trained and supervised raters can demonstrate high reliability, reports from school psychologists, occupational therapists, and others consistently report scoring “by eye”, which introduces a substantial likelihood of scoring errors.

B. The Future of VMI Assessment

Advances in technology have changed the landscape of many assessments, particularly for administration on devices. However, many of these tools still require the examiner to manually score responses before inputting the results into the system for interpretation.

Assessing VMI digitally provides substantial benefits and overcomes common limitations of paper-and-pencil visual-motor tests. Computer administration and scoring can eliminate common problems of paper-and-pencil tests, such as:

● Lack of a standardized test environment

● Risk of subjectivity in scoring responses

● Likelihood of human error

● Lower inter-scorer and test-retest reliability

● Underestimation of examinees' performance

● Loss of valuable time

● Inconvenience of transporting test materials and booklets between settings

Changing the status quo of VMI assessment to address the current obstacles is the goal of Psymark’s new Visual-Motor Abilities Test, presented next.

III. Psymark’s Visual-Motor Abilities Test (VMAT): A Digital Solution

A. Introducing Psymark’s Visual-Motor Abilities Test (VMAT)

The VMAT was created by a highly experienced team of school psychologists, researchers, software engineers, and business leaders. Born from their own personal experiences, the team is following their mission to make assessment better for practitioners and better for examinees.

Downloaded as an App, and administered and scored on an iPad within minutes, the VMAT was developed to substantially improve visual-motor assessment. The VMAT is the first digital standardized visual-motor assessment test for the evaluation of visual-motor skills of children ages 4 to 9. It is used by occupational therapists, school psychologists, mental health clinicians, and other health care professionals in the diagnosis and identification of visual-motor skill deficits.

B. Comprehensive, Robust Features

The VMAT has several stand-out strengths:

● It is quickly and easily administered on the iPad and self-scores within 4 to 6 minutes. Allows more assessments to be conducted in a shorter timeframe.

● Secure by design

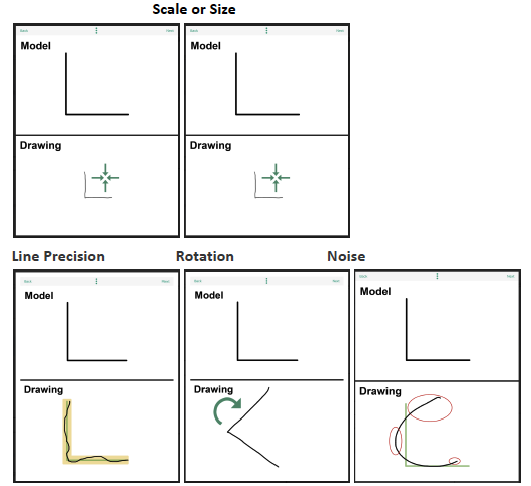

● Dynamically measures multiple features associated with visual-motor abilities and deficits. o Features include Rotation, Sizing or Scale, Line Precision (i.e., lines drawn within the expected range), and Noise (i.e., extraneous lines).

● Provides supplementary descriptive data for the examiner’s consideration of additional factors that may impact visual-motor performance. o Includes data on average speed of the drawing tasks, allowing examiners to consider the time required to complete the tasks and speed at which each examinee completes the drawing. It also reports on the examinee’s contact time with the screen and the number of times the examinee lifts his or her finger or stylus from the iPad.

● Automatically scores and generates performance results and graphs that can be printed and saved as a PDF to the examiners’ files, and easily added to evaluation reports.

● Provides key data for special education qualification. Ideal for MTSS Tiered Interventions.

● Addresses the drawbacks of paper-pencil around testing standardization, subjectivity, human error, low reliability, and loss of valuable time.

● Offers a free trial for the first 100 tests, virtual or in-person training, and customer support.

C. State of the Art Scoring

Psymark’s VMAT is self-scoring and uses a patented algorithmic scoring system, which generates a standardized visual-motor Performance score. The Performance score is an overall score from multiple specific measured features of visual-motor production. The Performance score is an overall score that can be interpreted as a summary of the visual-motor performance on the test. It is reported as a standard score and percentile.

The specific visual-motor features measured include:

● Scale or Size – the relative size of the drawing compared to the stimulus model

● Line Precision – A measure of the lines within the expected range given the stimulus model

● Rotation – the angular rotation of the drawing compared to the stimulus model

● Noise – parts of drawings or marks that are extraneous to the reproduction compared to the stimulus model

Here is how the Scoring Features look:

The VMAT goes much deeper. In addition to the overall performance score, the test reports descriptive information that may be helpful in describing how the examinee approaches the test:

● Number of Lifts - number of times the examinee lifted their finger or stylus off the screen

● Contact Time - time in seconds the examinee’s finger or stylus was in contact with the screen

● Average Speed - average speed the shapes are drawn in centimeters per second

D. Psychometrics

Reliability: Reliability centers around error. A reliable test produces similar results each time it is used under the same conditions, indicating low measurement error. High reliability ensures scores are dependable rather than the result of random chance or factors. Traditional visual-motor measures have had significant inter-rater reliability issues, as well as human error, which also reduces reliability.

Some assessments, such as the Beery VMI, even suggest that rulers and protractors are not often necessary. However, scoring ‘by eye’ is poor practice in the realm of reliability. The VMAT uses computer scoring, which has effectively solved the interscorer reliability issue. The computer scores the items with virtually perfect consistency, producing near-perfect reliability. Additional forms of reliability for the VMAT, including test-retest reliability, are currently the focus of ongoing research.

Validity: Validity is how accurately a test measures what it is designed to measure. The concurrent validity of the VMAT has been demonstrated in two studies to date (Fall, 2025; Berstein, 2025). Concurrent validity checks if a new test produces similar results to a known, validated one.

When compared to the Beery VMI (6th ed), the VMAT has a correlation of .76 (moderately high) with a sample of young children and adults. With children ages 4 to 6, the correlation was .64 (moderate to strong), and with children ages 5 to 17, the correlation was .51 (moderate). Younger children had a lower percentage of scorable items than older children. Based in part on this finding, the Psymark VMAT scoring has been modified to include an adjustment to scores based on the number of items found to be unscorable.

Comparing paper-pencil to tablet: The question of whether the VMAT experience for examinees differs from tablet to paper-pencil assessment was explored with 5 to 96-year-olds. Results from three conditions of Traditional paper-and-pencil, Stylus on iPad, and Finger on iPad, indicated remarkable similarity in drawing produced in all three conditions.

Of the 75 variables measured, none had statistically significant differences across mode of presentation or for any measured elements within any item, such as angles, lengths of lines, etc. These findings strongly indicate the cognitive and visual-motor process of drawing geometric figures on the iPad is functionally the same as when using pencil and paper.

Other research has shown that tests taken on paper can significantly underestimate the performance of students who are adapted to using digital devices (Russell & Haney, 2000)

E. Standardized Norms

Standardization of norms is a crucial element of assessment—ensuring tests are accurate in identifying how a test-taker ranks in comparison with peers. When norms are outdated, this goal is compromised. Post-COVID studies on fine and gross motor, as well as reports from educators, occupational therapists, and other professionals, have noted changes in skill development (Backman et al., 2025; Kotzsch et al., 2025).

One driving reason is that the availability and children’s access to screens are believed to have potentially changed children’s visual-motor abilities. Children in the past spent much of their playtime using pencils, crayons, playdough, scissors for crafts, climbing, and so on. Now, many children spend an increased amount of time playing digital games and doing other activities on screens. Excessive screen time in children is generally associated with negative impacts on fine motor skills through replacing hands-on, three-dimensional play activities essential for developing dexterity, hand strength, and coordination (Bakht et al., 2025).

This trend and impact on visual-motor abilities highlight the need for Post-Covid normative data for an accurate evaluation of children’s current skills. Initial standardization of VMAT began in 2024 following the Covid lockdowns and therefore provides Post-Covid standardization norms. In 2024 to early 2026, normative data were gathered from 1,671 children ages 4-9 across twenty-seven states in all four regions of the United States. National standardization continues for children ages 10-12 and is anticipated to be completed by spring of 2026.

Creating a new assessment represents a substantial effort, and developing a comprehensive digital platform even more so. The Psymark VMAT has gone through each stage in a careful, rigorous manner.

IV. Summary

Assessment is a central responsibility for professionals, one that they, and the team at Psymark, take very seriously. Visual-motor assessment has been a part of cognitive assessment for over 100 years. It is in this spirit that the VMAT takes its place as the first standardized VMI assessment product developed by Psymark—and as a highly evolved version. Built using the power of device technology, greater accuracy and precision, the most up-to-date norms, and richer data, the VMAT offers a far better experience for examiners and examinees.

Why VMAT? Why Now? Children’s visual-motor demands have changed. Eligibility decisions are rising. Assessment practices have not kept pace. The VMAT brings visual-motor assessment to a new level. One that supports the modern realities and needs of today’s professionals.

We invite you to visit www.psymark.ai to learn more about the mission, product, and research behind the VMAT.

V. References

Arundel, C. (2025, February 25). Special education climbs to nearly 8 million. K–12

Dive.https://www.k12dive.com/news/number-of-special-education-students-climbs-to-near-8-m

illion/740413/

Backman, E., Lundberg-Ulfsdotter, R., Silfverdal, S.-A., West, C. E., & Domellöf, M. (2025). Effects of the

COVID-19 lockdowns on gross motor and fine motor neurodevelopment in toddlers. Acta Paediatrica, 114(12), 3332–3341. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.70266

Bakht, D., Yousaf, F., Alvi, Z., Buhadur Ali, M. K., Khawar, M. M. H., Munir, L., Bokhari, S. F. H., Qureshi, M.

S., Raza, M., & Qureshi, A. A. (2025). Assessing the impact of screen time on the motor development of children: A systematic review. Pediatric Discovery, 3(2), e70002. https://doi.org/10.1002/pdi3.70002

Beery, K. E., & Beery, N. A. (2010). Beery Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration (6th ed.). APA

PsycTests.

Bender, L. (1938). A visual motor Gestalt test and its clinical use (Research Monographs, American

Orthopsychiatric Association, No. 3). American Orthopsychiatric Association.

Bernstein, K.(2025). Psymark Shapes visual-motor progress monitoring tool: A validation study.

Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Yeshiva University.

Blad, E. (2025, December 19). 50 years of IDEA: Four things to know about the landmark special

education law. Education Week.

Brannigan, G. G., & Decker, S. L. (2003). Bender Gestalt II: Bender Visual-Motor Gestalt Test (2nd ed.).

Riverside Publishing.

Buchhave, P., Stomrud, E., Warkentin, S., Blennow, K., Minthon, L., & Hansson, O. (2008). Cube copying

test in combination with rCBF or CSF Aβ42 predicts development of Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 25, 544–552. https://doi.org/10.1159/000137379

Carlson, A. G., Rowe, E., & Curby, T. W. (2013). Disentangling fine motor skills’ relations to academic

achievement: The relative contributions of visual–spatial integration and visual–motor

coordination. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 174(5), 514–533.

Carsonne, B., Green, K., Torrence, W., & Henry, B. (2021). Systematic review of visual motor integration in

children with developmental disabilities. Occupational Therapy International, 2021, Article 1801196. http://doi.org/10.1155/2021/1801196.

Cormack, F., Aarsland, D., Ballard, C., & Tovee, M. (2004). Pentagon drawing and neuropsychological

performance in dementia with Lewy bodies, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease with dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 19, 371–377.

Cornhill, H., & Case-Smith, J. (1996). Factors that relate to good and poor handwriting. American Journal

of Occupational Therapy, 50(9), 732–739.

Dere, Z. (2019). Analyzing the early literacy skills and visual motor integration levels of kindergarten

students. Journal of Education and Learning, 8(2), 176–181. https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v8n2p176

Dohla, D., & Heim, S. (2016). Developmental dyslexia and dysgraphia: What can we learn from the one

about the other? Frontiers in Psychology, 6, Article 2045.

http://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.09045

Fall, R. (2025, October). Concurrent validity of the Psymark Shapes Test and the VMI. Paper presented at

the annual meeting of the California Association of School Psychologists, Santa Ana.

Keane, B. P., Paterno, D., Kastner, S., & Silverstein, S. M. (2016). Visual integration dysfunction in

schizophrenia arises by the first psychotic episode and worsens with illness duration. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(4), 543–549.

Khatib, L., Li, Y., Geary, D. C., & Popov, V. (2022). Meta-analysis on the relation between visuomotor

integration and academic achievement: Role of educational stage and disability. Educational Research Review, 35, 100412.

Kluger, A., Gianutsos, J. G., Golomb, J., Ferris, S. H., George, A. E., Franssen, E., & Reisberg, B. (1997).

Patterns of motor impairment in normal aging, mild cognitive decline, and early Alzheimer’s disease. Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 52(1), P28–P39.

Kotzsch, A., Papke, A., & Heine, A. (2025). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the development of

motor skills of German 5- to 6-year-old children. Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), Article 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030353

Lo, S. T., Collin, P. J. L., & Hokken-Koelega, A. C. S. (2015). Visual–motor integration in children with

Prader–Willi syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 59(9), 827–834.

Maeshima, S., Itakura, T., Nakagawa, M., Nakai, K., & Komai, N. (2004). Visuospatial impairment and

activities of daily living in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A quantitative assessment of the cube-copying task. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 76(5), 383–388.

National Center for Education Statistics. (n.d.). Digest of Education Statistics: Table 204.30.

https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d23/tables/dt23_204.30.asp

Palmqvist, S., Minthon, L., Wattmo, C., Londos, E., & Hansson, O. (2010). A quick test of cognitive speed

is sensitive in detecting early treatment response in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy, 2, Article 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/alzrt53

Pieters, S., Desoete, A., Roeyers, H., Vanderswalmen, R., & Van Waelvelde, H. (2012). Behind

mathematical learning disabilities: What about visual perception and motor skills? Learning and Individual Differences, 22(4), 498–504.

Russell, M., & Haney, W. (2000). Bridging the gap between testing and technology in schools. Education

Policy Analysis Archives, 8(19). https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v8n19.2000

Schlooz, W. A. J. M., & Hulstijn, W. (2012). Atypical visuomotor performance in children with pervasive

developmental disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(1), 326–336.

Schneck, C. M., Case-Smith, J., Allen, A. S., & Pratt, P. (1996). Visual perception. In J. Case-Smith (Ed.),

Occupational therapy for children (3rd ed., pp. 357–386). Mosby.

Schultz, R. T., Carter, A. S., Gladstone, M., Scahill, L., Leckman, J. F., Peterson, B. S., & Pauls, D. L. (1998).

Visual–motor integration functioning in children with Tourette syndrome. Neuropsychology, 12(1), 134–145.

Volker, M. A., Lopata, C., Vujnovic, R. K., Smerbeck, A. M., Toomey, J. A., Rogers, J. D., Schiavo, A., &

Thomeer, M. L. (2010). Comparison of the Bender–Gestalt II and VMI–V in samples of typical children and children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 28(3), 187–200.

Psymark, Inc.

9100 Wilshire Blvd, Suite 333 #2, Beverly Hills, CA 90212

info@psymark.ai I 888-339-6112